Driving the Nuclear Power Plant

Acquiring the skill to operate a nuclear reactor bears resemblance to acquiring the skill to pilot an aircraft. The majority of airplane pilots rapidly acquire proficiency in performing take-offs and landings. The process that requires significant time and exertion, particularly for sizable passenger airplanes, is acquiring the knowledge and skills to effectively address unexpected issues. The situation is identical when it comes to a nuclear reactor.

The nuclear power plant is equipped with numerous automated devices that facilitate its operation. The reactor is equipped with reliable monitoring systems that can be trusted to initiate shutdown procedures and implement other precautionary measures in the case of a significant incident.

An operator plays a crucial role in overseeing the plant’s operations, proactively preventing issues whenever possible, promptly addressing any incidents, and mitigating their potential impact on the environment.

Several occurrences are probable to occur during the lifespan of a nuclear power facility. One of the most common consequences is the disruption of a power grid.

- What Happens if the Grid Power Goes Down?

- Natural Circulation Around the Primary Circuit

- Batteries and Back-Up Diesel Generators

- Running Pumps

- Recovering From a Loss of Grid

- BONUS! Download Guidebook to Modern Instrumentation and Control for Nuclear Power Plants (PDF)

1. What Happens if the Grid Power Goes Down?

Let us commence with a simple task. Envision yourself operating your reactor at a consistent and maximum level of power when, unexpectedly and without any prior indication, you experience a disconnection from the electrical grid.

What could be the cause of this occurrence?

Could it be that a storm has caused damage to certain power transmission lines, or that a significant substation has had a fire? Or maybe the main power substation has been bombed, like we saw in certain war recently. If a sufficient number of gridlines in your area are impacted by these issues, you may abruptly lose connection to the grid.

For what reason?

There is a significant correlation between the length of a power line and the probability of an electrical fault, with longer lines appearing to be more prone to such issues. After operating the plant for a few of decades, the operator will likely have an accurate understanding of the local fluctuations in grid frequency.

Upon entering the control room, the initial sights that he is likely to encounter are the alarms and indicators signaling a turbine and reactor shutdown. The operator should promptly recognize that this is not an ordinary reactor trip…

In the event of a power outage and the turbine shutting down, the facility will be unable to provide the necessary high voltage electricity to power the motors of the huge pumps, and that’s not good.

Figure 1 – Nuclear Power Plant Control Room

Based on the specific nuclear plant design, it is reasonable to speculate that the operator has experienced a loss of electrical power owing to:

- The circulating water pumps that deliver seawater to plant’s turbine condensers

- The primary feedwater pumps that typically provide steam to the steam generators

- The reactor coolant pumps (devices used to circulate coolant in a nuclear reactor)

If the sea-water pumps fail, the vacuum in turbine condensers will deteriorate rapidly. Initially, the operator may release steam to these devices shortly after the trip. However, after a sufficient amount of vacuum is lost, this will no longer be feasible.

The loss of the main feedwater pumps may appear to be a significant issue, yet it is not overly problematic. The reactor shutdown has halted the ongoing chain reaction, therefore requiring the operator to solely manage the removal of decay heat from the core.

Although this heat amounts to several megawatts, it constitutes just a small fraction of the reactor’s overall output.

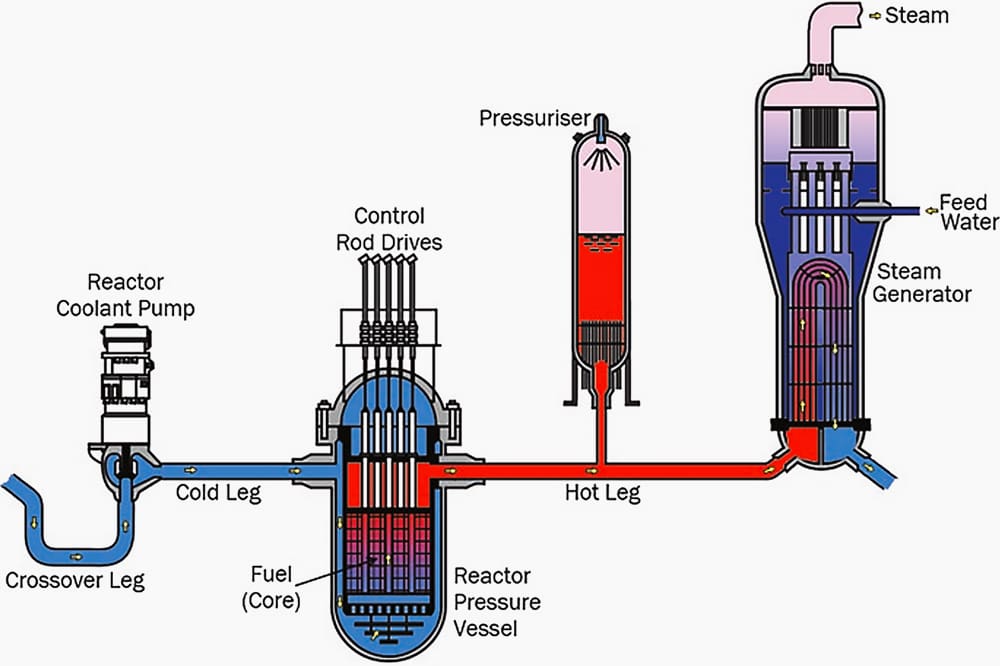

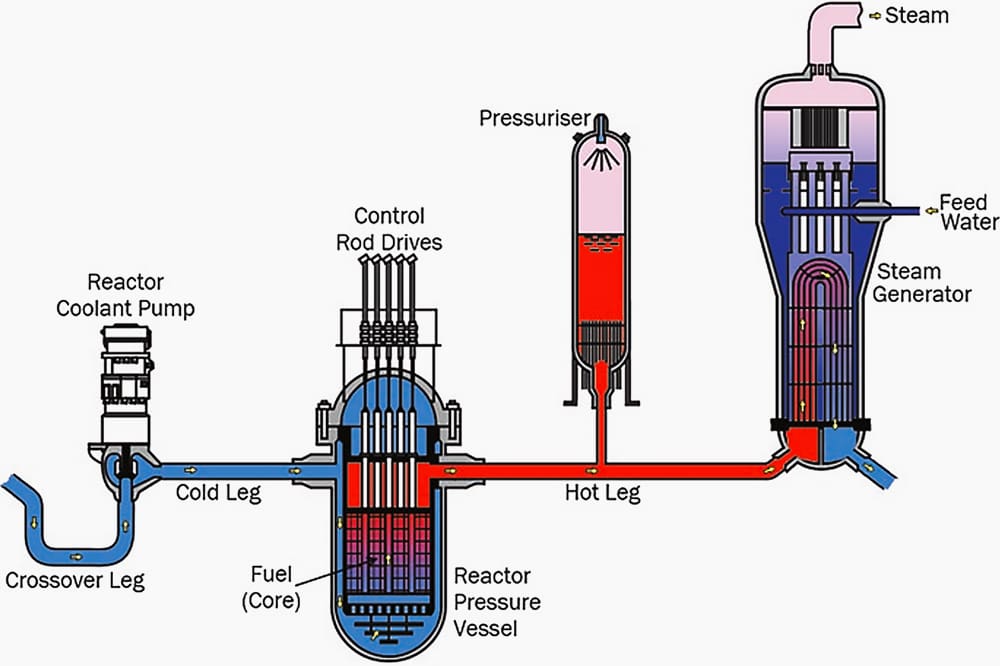

Figure 2 – Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR) primary circuit cooling loop

Lesser auxiliary feedwater pumps have the capacity to provide sufficient feedwater to the steam generators for effective management.

What’s happening with the reactor coolant pumps? The reactor coolant pumps are equipped with large electric motors, making it impractical to maintain their operation during a power grid failure. Every reactor coolant pump is equipped with a flywheel, which results in a gradual deceleration over a short period of time rather than an immediate stop.

Are we not depending on these mechanisms to facilitate the flow of water through the core and maintain the cooling of the reactor, even during its shutdown? Typically, such is the case. However, in the event of a power grid failure, that is not a viable choice.

Instead, you will need to rely on the principles of physics.

2. Natural Circulation Around the Primary Circuit

As the reactor coolant pumps decelerate and come to a halt, the rate of water circulation within the core decreases. As the process continues, the quantity of heat produced by decay and transferred to every kilogram of water will increase, resulting in a higher temperature difference (Thot minus Tcold).

Consequently, the water at the upper part of the core of the deactivated reactor would be hotter compared to the scenario when the reactor coolant pumps were still operational. The lower density of warmer water compared to colder water in the steam generator tubes causes the colder water to displace the warmer water by descending out of the tubes.

The primary circuit’s architecture is well-suited for this purpose, as it involves positioning a high-temperature reactor at a lower level and placing colder steam generators at higher elevations.

Figure 3 – Regular reactor operation, water recirculates in the primary loop

Furthermore, there exists a clear and unimpeded pathway starting from the upper part of the reactor, passing through the hot legs, reaching the tubes of the steam generators, and then returning through the crossover and cold legs to the lower part of the reactor.

The flow of water around the primary circuit is referred to as ‘natural circulation‘ since it is only driven by temperature and density disparities, rather than by the use of pumps (similar to the secondary side of the steam generators).

Usually, a Pressurized Water Reactor will achieve this state within a time frame of less than 15 minutes following a grid failure, exhibiting a temperature difference around half of what is observed at full power, as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4 – Natural circulation

There is no necessity to regulate any of this; the laws of physics dictate that the primary circuit will naturally achieve its own state of balance. Moreover, as the decay heat diminishes, the natural circulation will also decrease, without requiring any intervention on your side. The initial stages of Thot‘s decline can be observed in Figure 4.

You may be curious about the factors that maintain a consistent low temperature (Tcold) during this event.

The steam is being released through the Pressure Operated Relief Valves.

The steam dumping holds steam pressure in the steam generators constant. This fixes the temperature as the steam generator is stuck on the boiling curve, and this, in turn, fixes Tcold.

3. Batteries and Back-Up Diesel Generators

Backup power MUST be considered. There is likely not much in the way of backup power in your home. However, if you happen to have any electrical equipment with built-in batteries, they will continue to function (or at least keep the time) in the event of a power outage. A backup generator is usually not in your possession, unless you happen to reside in a particularly remote area.

A nuclear power plant has a very different backup power need. You don’t want to lose the nuclear power plant’s instrumentation, computers, controls, and protection systems in the event of a grid outage, therefore you’ll also need to have plenty of big batteries on hand to supply low voltage electricity continuously.

Pressurized water reactors typically use diesel generators, although gas turbines (jet engines) are also used by some units. It is common to see pressurized water reactors. The typical configuration consists of four massive “Essential Diesel Generators“, each of which can generate 5–10 MW of electrical power. Figure 5 shows an example of this.

That may sound like a lot, but you’ll see that they have to power a lot of equipment for a more major defect.

Figure 5 – Essential diesel and generator in the nuclear power plant

But it is insufficient to initiate the coolant pump in a reactor. Four diesel generators – why?

This method is comparable to other safety measures. If you have four diesel generators to begin with, you can take one out for maintenance and still handle the situation if another one doesn’t start. This is important because your safety case needs to demonstrate that you can handle any fault (including a loss of grid) with just one or two operational generators.

4. Running Pumps

Once diesel generators have started, which is something you would expect to be happening very quickly and automatically when the grid is lost, you will have access to electrical power that will allow you to keep your batteries charged and to run some of the medium-sized pumps, such as auxiliary feedwater pumps and Chemical and Volume Control System pumps.

On the other hand, you can’t turn on all of this machinery at the same time because doing so would cause the diesel to stop working.

These automatic systems will instead be required to sequence the electrical loads onto the engine over the course of a few minutes in order to ensure that the diesel engine is able to respond without stalling.

These steam-driven pumps are important since they do not require diesel generator supplies in order to function. As a result, they would be accessible even if none of the plant’s diesel generators started up in the event of a loss of grid. In light of the fact that steam-driven pumps typically require a significant amount of maintenance, it is important to note that certain reactor designers do not favor them.

The alternative would be for these designers to equip a reactor with a greater number of diesel generators, with some of them being constructed according to distinct designs. This would ensure that no single issue would effect all of your diesel generators at the same time.

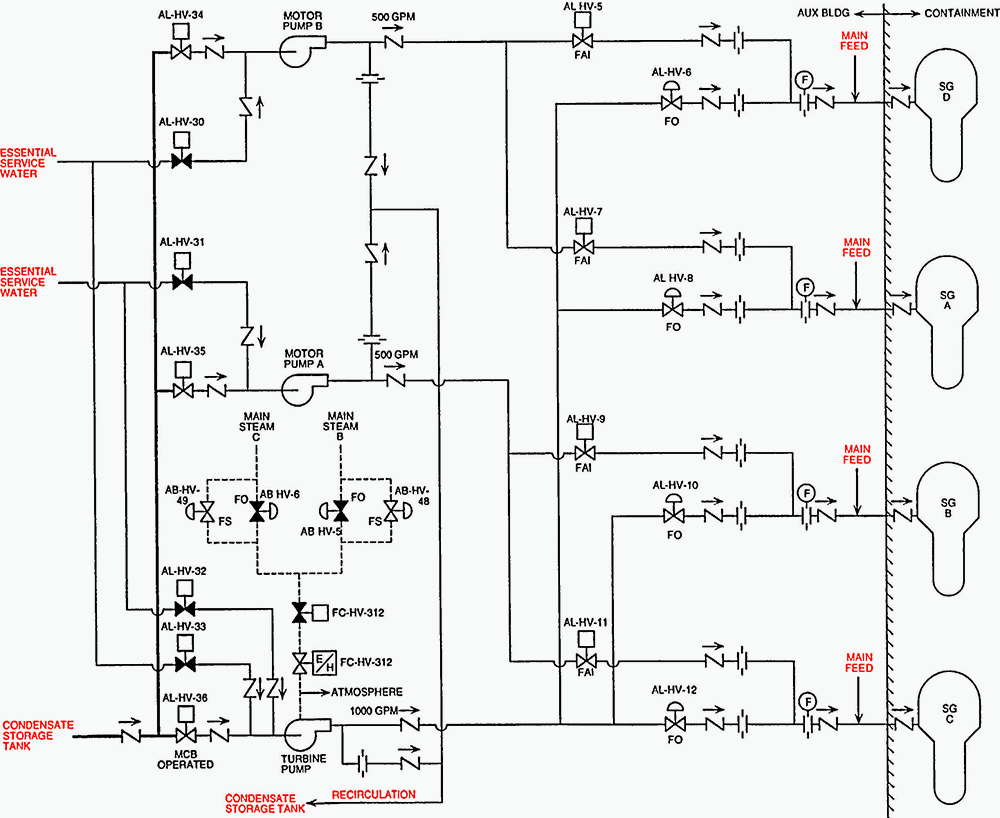

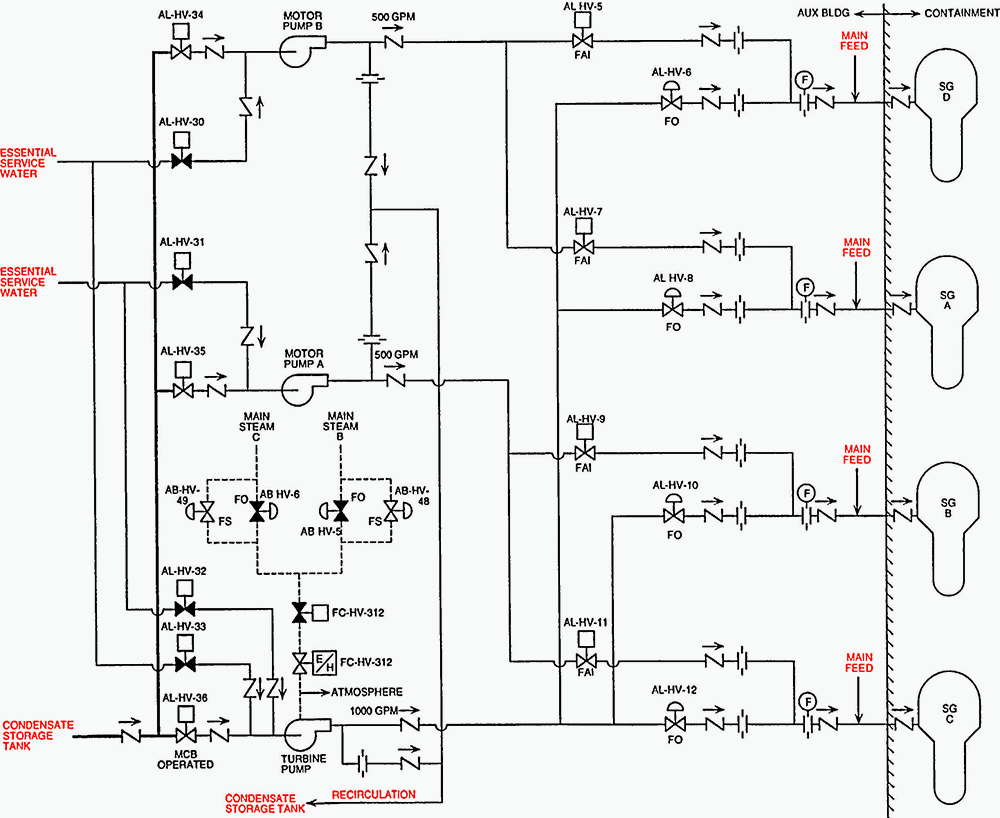

Figure 6 – An example of the auxiliary feedwater system

6. Recovering from a Loss of Grid

It is impossible to switch on the Pressurized Water Reactor if there is no supply of electricity coming from the grid. Even if diesel generators were able to be attached, the mere act of attempting to start a reactor coolant pump would cause them to become inoperable. It is necessary for all four reactor coolant pumps to be operational before your Reactor Protection System will allow you to reset the trip.

This means that you do not have the option to “black-start“, in contrast to certain coal and gas stations that are able to resume operations without the assistance of grid supplies.

It’s possible that the operator will believe that he can simply reconnect the electrical system of your station to the offsite supply once the grid has been established again. In actuality, this would result in a dilemma that is quite comparable to the struggle of trying to connect all of the plant loads to a diesel generator that is operating.

Figure 7 – Reactor coolant pump motor set up for final performance test

The operator would discover that the current would be too high as a result of trying to start-up all of the equipment on the plant system at the same time. As a result, he would most likely blow a fuse (or some other more sophisticated sort of electrical protection) rather than stalling an engine. The only choice available to the operator is to begin at the electrical panelboards on the station that have the highest voltage and then disconnect everything that is leading from those panelboards.

After he has completed this step, the operator will be able to connect those panelboards to the grid in a secure manner, and then to rejoin the outgoing circuits one at a time. It will be necessary for him to repeat this procedure each time you attempt to re-energize a panelboard, all the way down to the pieces of equipment and boards that have the lowest voltage.

This won’t be a quick process; it will most likely take twenty-four hours before everything is back up and running. After that, he will be able to consider firing up the reactor at the factory.

Suggested Reading – A roadmap for engineers seeking mastery in the language of electrical schematics

A roadmap for engineers seeking mastery in the language of electrical schematics

6. BONUS! Download Guidebook to Modern Instrumentation and Control for Nuclear Power Plants (PDF)

Download BONUS: Download Guidebook to Modern Instrumentation and Control for Nuclear Power Plants (648 pages, PDF) (for premium members only):

Source: How to Drive a Nuclear Reactor by Colin Tucker