Reading and interpreting drawings

Engineering tasks require a good skill in reading and interpreting information on drawings. Engineering drawings are the industry cornerstone of conveying detailed and precise information on how to construct, troubleshoot, maintain, and operate a system. Basic requirements are needed to understand the way of reading these drawings: rules, basic symbols, and industry conventions.

That being said, a pre-requisite of learning how to read the drawings is to know how to read non-drawing areas of a print. Vendors have variant drawing formats and information, so all drawings will have different information from these addressed here, but these drawings are usually similar.

This article provides tips for different drawing types that help to grasp these drawings’ main principles quickly. These drawings cover single-line, schematic, wiring, logic, and P&ID drawings that are found in the industry. Prior to delving into more details of these drawings, non-drawing topics are usually overlooked in explaining the drawing reading basics.

Then, the mentioned drawing types are introduced and some tips are presented to help to interpret these drawings. This article does not explain these drawings, instead one must have some sort of basic understanding of the drawings.

1. Drawing Anatomy

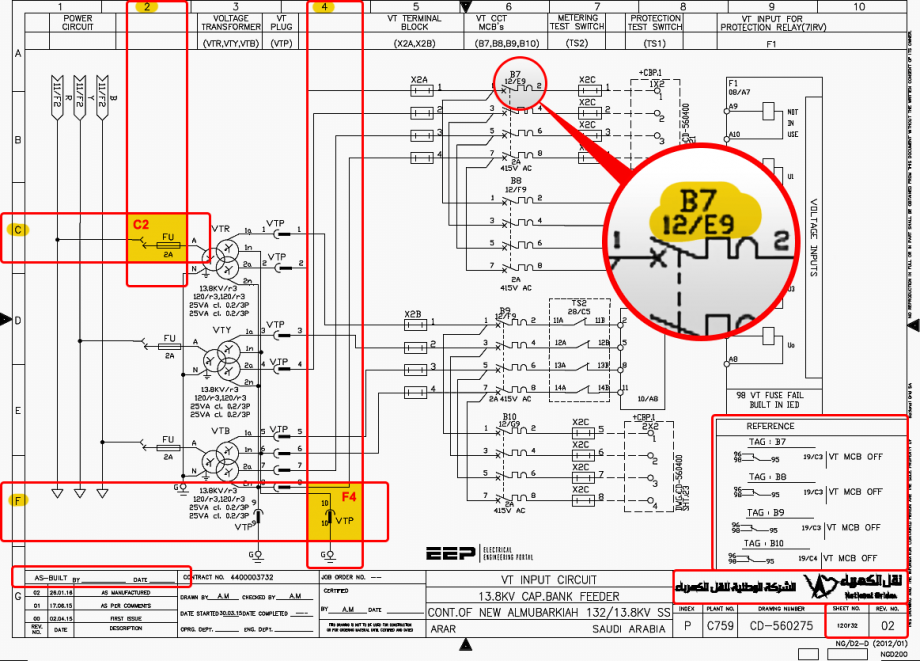

Engineering drawings are classified into the following areas:

- Title block

- Grid system

- Revision block

- Notes and legends

- Engineering drawing (graphic portion)

The first four items represent the non-drawing parts that are essential in reading the drawing itself. Hence, a brief description of each item is presented in this article.

1.1. Title Block

A title block is normally located at the bottom of a print, lower right-hand corner in particular. It has the all necessary information to identify drawings and verify their validities. Several areas comprise a title block as shown in Figure 1.

1.1.1. Title block first area

This area contains the drawing title, number, location, site, or vendor. The drawing title and the drawing number are used to identify and fill the required drawing. The drawing number is usually unique and consists of a code containing information about the drawing like site, drawing type, and system.

1.1.2. Title block second area

The second area encompasses the signatures and the dates of approval that provide information about when and who verified the drafted drawing for final approval. This information is invaluable in finding further data on the system design. Also, these referees can be helpful in discrepancy resolution and dispute settlements.